Outpatient Treatment for Osteoporotic Pelvic Fractures

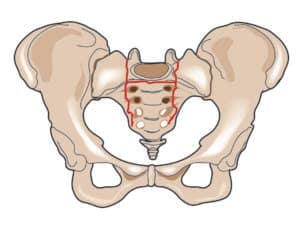

Pelvic fractures, also known as insufficiency fractures, are common osteoporotic fractures of the pelvis and are often overlooked or misdiagnosed. The most common of these pelvic fractures involves the sacrum, known as a sacral insufficiency fracture. Although other parts of the pelvis may suffer similar fractures, this article describes the symptoms, diagnosis, and available treatments for sacral insufficiency fractures.

The Problem

In a sacral insufficiency fracture, the bone is weakened, usually from osteoporosis, to the extent that it gives way with only body weight or minimal trauma. Sacral insufficiency fractures have existed as long as osteoporosis but have received less attention than back and hip fractures. In fact, this condition was only first described in literature in 1982.(1) One reason this diagnosis was not recognized is the nonspecific, but sometimes severe, symptoms. The symptoms overlap with that of other low back problems, such as disc herniation, facet arthritis, and compression fractures.For example: When an elderly patient presents to the emergency room, the first test usually ordered by an ER physician is an X-ray. When testing for a sacral insufficiency fracture, an X-ray will almost always be normal. Since the X-ray result is “negative,” the patient is often sent home or even kept in the hospital with continued pain and no diagnosis.

Another reason for recent recognition of sacral insufficiency fractures as a diagnosis is that sophisticated imaging studies such as MRIs, CTs, and bone scans were not introduced until the 1970s and 1980s. One of these three sophisticated imaging studies is needed to accurately make the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Sacral insufficiency fractures are difficult to diagnose. When a previously active elderly patient, more commonly a female, presents with severe new pain in one or both buttocks and is unable to move about, the patient should be considered to have a sacral insufficiency fracture until proven otherwise. Symptoms are often insidious with no known event. Other times, symptoms start after a minor fall on the buttocks, a misstep off a curb, or sitting down too hard. The pain may radiate to the groin or down the back of the leg.

An MRI is the best test to diagnose a sacral insufficiency fracture. Often, however, a routine lumbar MRI is ordered, which includes only a small upper portion of the sacrum. If a patient is not able to have an MRI, a CT is the second best test to diagnose the fracture. Even with a CT test, a sacral insufficiency fracture can be very subtle and often missed, unless there is a high index of suspicion by the radiologist. Another test to diagnose a sacral insufficiency fracture is the radionuclide bone scan. Radionuclide bone imaging is sensitive for these fractures but unfortunately does not show the actual fracture, just the abnormal bony activity or “hot spot.”

Conservative Treatment

Conservative treatment, which is usually started when the initial diagnosis is made, was the only treatment until 10 years ago. However, it is not without risk. Because this involves bed rest, partial weightbearing, and pain medication, there are risks of deep venous thrombosis (the formation of a blood clot in a deep vein), pulmonary embolism (blockage in one or more arteries of your lungs), decrease in muscle strength, pneumonia, and depression. Pain medication can cause significant constipation in this patient population. Elderly patients lose 10 percent of their muscle mass for every week of bed rest. Mental depression can be significant if immobilization is prolonged in a previously independent person.

Enter Sacroplasty

Sacroplasty as a treatment for sacral insufficiency fractures was first described in 2002.(2) The procedure is an extension of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, which have gained acceptance as treatments for vertebral compression fractures. Injection of bone cement into a vertebral compression fracture originated in France in 1987,(3,4) but was not popularized until the 1990s in the United States.(5) Sacroplasty lagged behind in popularity for several reasons. One of these reasons is that sacral insufficiency fractures were less likely to be recognized and were thought to be shear fractures as opposed to compression fractures. A second reason is the technique of sacroplasty is more technically challenging due to the complex shape of the sacrum.

Sacroplasty is performed as an outpatient procedure with minimal to no sedation. Using local anesthesia, a needle is placed into the largest part of the sacrum called the sacral ala. This can be performed with fluoroscopic or CT guidance; both methods have advantages. Once the needle is in the proper location, polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA – bone cement) is mixed and slowly injected into the fractured area. The cement hardens within an hour. The patient lies prone or supine for the hour after the procedure. Once the hour passes, the patient may ambulate, usually with much less pain than before the procedure.

Complications, which are very unlikely, include the chance of bleeding or infection, like any other invasive procedure. There is also a very slight chance that the cement may leak out of the proper fractured area into a vein or nerve canal.

Post-procedure care is minimal. Driving on the day of the procedure is not allowed due to the possible use of sedatives. Normal activity with routine osteoporotic precautions can be resumed the next day. If there has been a delay of treatment or diagnosis for more than a couple of weeks, or if the patient has been debilitated, physical therapy and/or rehabilitation may be needed to build strength and regain mobility.

Richard E. Kinard is Board Certified in Diagnostic Radiology. Dr. Kinard specializes in Sacroplasty, Kyphoplasty, and Diagnostic and Therapeutic Spinal and Joint Injection procedures. He attended medical school at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and completed his residency training at David Grant USAF Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base in California. Dr. Kinard is an active member of the American College of Radiology, Radiological Society of North America, North American Spine Society, and International Spinal Intervention Society.

References:

- Lourie H. Spontaneous osteoporotic fracture of the sacrum: An unrecognized syndrome of the elderly. JAMA. 1982;1982(248(6)):715-7.

- Garant M. Sacroplasty: a new treatment for sacral insufficiency fracture. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2002;13(12):1265-

Galibert PD, H.; Rosat, P.; Le Gars, D. Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty. Neurochirurgie. 1987;1987(33(2)):166-8. - Peters KR, Guiot BH, Martin PA, Fessler RG. Vertebroplasty for osteoporotic compression fractures: current practice and evolving techniques. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(5 Suppl):S96-103. Epub 2002/09/18. PubMed PMID: 12234436.

- Jensen ME, Evans AJ, Mathis JM, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, Dion JE. Percutaneous polymethylmethacrylate vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral body compression fractures: technical aspects. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 1997;18(10):1897-904. Epub 1997/12/24. PubMed PMID: 9403451.